Vampires are real, and they exist in all pockets of society. But is drinking blood safe? What does the science say about sipping on blood?

We humans, we're all just flesh and blood. And as we've already covered the costs of consuming flesh, let's have some banter about imbibing blood.

Inside your vessels (blood vessels that is, not drinking vessels), blood carries just about everything your body needs. It picks up oxygen from the lungs and nutrients from the gut and hand delivers them to your cells.

An online vampire research portal, with resources and information, terminology, folklore and historical writings, and otherkin related materials. All topics covered here deal with vampires and similar cryptids.

Text of Prince Dracula

Editor's Note: This text is a translation of one of the oldest surviving versions of the story of Vlad V, Prince of Wallachia--known to his friends as Vlad the Impaler, or Prince Dracole. It was printed in Nuremburg in 1488. The accounts of the atrocities here must be taken with a grain of salt, since this pamphlet and many other like it were prepared under the influence of a political enemy of Vlad V, King Matthias Corvinas of Hungary. The document was written within a few years of Vlad V's death, however, and some of the events described can be traced back to events in historical records.

Six copies of this particular pamphlet are known to exist. The only copy outside of Europe--from which this translation was made--is held by the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia. This translation is from a publication prepared by the Rosenbach Museum and Library.

Vampire myths originated with a real blood disorder

The concept of a vampire predates Bram Stoker's tales of Count Dracula—probably by several centuries. But did vampires ever really exist?

In 1819, 80 years before the publication of Dracula, John Polidori, an Anglo-Italian physician, published a novel called The Vampire. Stoker's novel, however, became the benchmark for our descriptions of vampires. But how and where did this concept develop? It appears that the folklore surrounding the vampire phenomenon originated in that Balkan area where Stoker located his tale of Count Dracula.

Video submission: The Strange Origin Of Vampires

Submitted by: Benjamin Michael

Have you ever wondered where vampire legends came from? It turns out the origin is pretty strange and unexpected, and the creature you're used to thinking of isn't much like how they began.

Vampires weren't always the pale, gaunt figure we think of when we see them today. And they definitely weren't glittery teenagers. They were something much more primal, and ugly, and... Weird.

The vampire you think of today was inspired by Bram Stoker's novel, Dracula. But the first appearance of the word vampire was almost 200 years earlier, so what did they look like in that time? Keep watching to find out!

Fact or Fiction: Are Vampires Real?

Raise the stakes with this all encompassing guide on all things vampires.

Author: Leah Hall, for Country Living

It's not your imagination: Vampires are everywhere. They're in vampire movies (hello, Interview with the Vampire) and all over television (we see you, The Vampire Diaries). They're the subject of countless books. (Twilight may have spawned a million vampiric copy cats, but if you want to get good and scared, try a classic: Stephen King's Salem's Lot.)

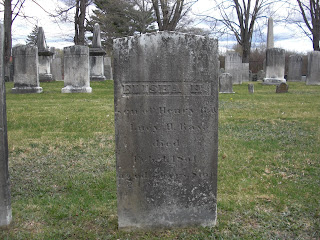

Jewett City Vampires

Connecticut: In the first half of the 19th century, Henry and Lucy Ray of Jewett City had a comfortably-sized family of five children who all grew up and survived the many natural perils and hardships of childhood that were present in colonial America.

The Icelandic Translation of ‘Dracula’ Is Actually a Different Book

The mysteries of this Gothic classic aren’t over yet

The Icelandic version of Dracula is called Powers of Darkness, and it’s actually a different—some say better—version of the classic Bram Stoker tale.

Makt Myrkranna (the book’s name in Icelandic) was "translated" from the English only a few years after Dracula was published on May 26, 1897, skyrocketing to almost-instant fame. Next Friday is still celebrated as World Dracula Day by fans of the book, which has been continuously in print since its first publication, according to Dutch author and historian Hans Corneel de Roos for Lithub. But the Icelandic text became, in the hands of translator Valdimar Ásmundsson, a different version of the story.

The Icelandic version of Dracula is called Powers of Darkness, and it’s actually a different—some say better—version of the classic Bram Stoker tale.

Makt Myrkranna (the book’s name in Icelandic) was "translated" from the English only a few years after Dracula was published on May 26, 1897, skyrocketing to almost-instant fame. Next Friday is still celebrated as World Dracula Day by fans of the book, which has been continuously in print since its first publication, according to Dutch author and historian Hans Corneel de Roos for Lithub. But the Icelandic text became, in the hands of translator Valdimar Ásmundsson, a different version of the story.

The Great New England Vampire Panic

Two hundred years after the Salem witch trials, farmers became convinced that their relatives were returning from the grave to feed on the living

Children playing near a hillside gravel mine found the first graves. One ran home to tell his mother, who was skeptical at first—until the boy produced a skull.

Because this was Griswold, Connecticut, in 1990, police initially thought the burials might be the work of a local serial killer named Michael Ross, and they taped off the area as a crime scene. But the brown, decaying bones turned out to be more than a century old. The Connecticut state archaeologist, Nick Bellantoni, soon determined that the hillside contained a colonial-era farm cemetery. New England is full of such unmarked family plots, and the 29 burials were typical of the 1700s and early 1800s: The dead, many of them children, were laid to rest in thrifty Yankee style, in simple wood coffins, without jewelry or even much clothing, their arms resting by their sides or crossed over their chests.

Except, that is, for Burial Number 4.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)